50 câu hỏi

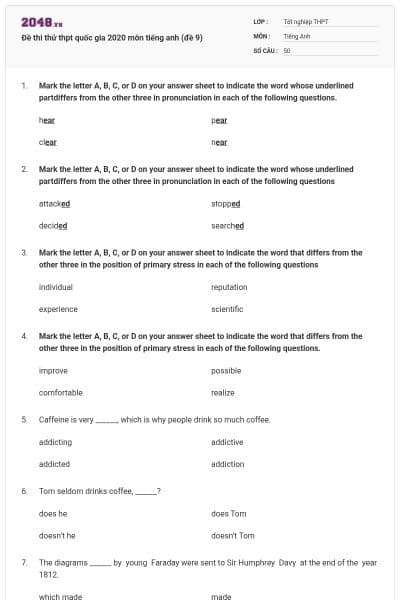

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the word whose underlined partdiffers from the other three in pronunciation in each of the following questions.

hear

pear

clear

near

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the word whose underlined partdiffers from the other three in pronunciation in each of the following questions

attacked

stopped

decided

searched

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the word that differs from the other three in the position of primary stress in each of the following questions

individual

reputation

experience

scientific

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the word that differs from the other three in the position of primary stress in each of the following questions.

improve

possible

comfortable

realize

Caffeine is very ______, which is why people drink so much coffee.

addicting

addictive

addicted

addiction

Tom seldom drinks coffee, ______?

does he

does Tom

doesn’t he

doesn’t Tom

The diagrams ______ by young Faraday were sent to Sir Humphrey Davy at the end of the year 1812.

which made

made

making

were made

Someone is going to have to take responsibility for this disaster. Who is going to ______?

foot the bill

carry the can

hatch the chicken

catch the worms

What noisy neighbors you’ve got! If my neighbors ______ as bad as yours, I ______ crazy.

are / will go

were / would go

had been / would have gone

are / would go

Apart from those three very cold weeks in January, it has been a very ______ winter.

pale

mild

calm

plain

The ______ of toothpaste are located in the health and beauty section of the supermarket.

quarts

pints

tubes

sticks

If orders keep coming in like this, I'll have to ______ more staff.

give up

add in

gain on

take on

You ______ for me; I could have found the way all right.

don’t have to wait

needn’t have waited

could have waited

didn’t need to wait

We've had to postpone ______ to France because the children are ill.

be gone

to go

going

go

In today’s paper, it ______ that there will be a new government soon.

writes

tells

states

records

His clothes are in a mess because he ______ the house all morning.

will have painted

will be painting

has been painting

had been painting

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the word(s) CLOSEST in meaning to the underlined word(s) in each of the following questions.

When the police arrived the thieves took to flight leaving all the stolen things behin

did away

climbed on

took away

ran away

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the word(s) CLOSEST in meaning to the underlined word(s) in each of the following questions.

Please, you are so nervous, do try to contain your anger.

hold back

consult

consume

contact

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the word(s) OPPOSITE in meaning to the underlined word(s) in each of the following questions.

I didn't take a deliberate decision to lose weight. It just happened.

calculated

planned

accidental

intentional

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the word(s) OPPOSITE in meaning to the underlined word(s) in each of the following questions.

The position fell vacant when Rodman was promoted.

bright

obscure

worthless

occupied

Jane and Suzie are talking after school.

Tom: “I’m awfully sorry I can’t go with you.”

Mary: “______? Haven’t you agreed?”

Why do you think

How come

What is it

Why don’t you

Peter and Mike are talking during a class break.

Peter: “What are you doing this weekend?”

Mike: “______.”

I’m very busy now

I plan to visit my aunt

I think it will be interesting

I hope it isn’t raining

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct word or phrase that best fits each of the numbered blanks from 23 to 27.

SOCIAL NETWORK

A 16-year-old girl from Essex has been sacked after describing her job as boring on the social networking website, Facebook. The teenager, who had been working (23) _________ an administrative assistant at a marketing company for just three weeks, didn’t feel very enthusiastic about the duties she was asked to do. (24) _________ of moaning to her friends she decided to express her thoughts on her Facebook page to a colleague, who (25) _________ the boss’s attention to it. He immediately fired her on the (26) _________ that her public display of dissatisfaction made it impossible for her to continue working for the company. She later told newspapers she had been treated totally unfairly, especially as she hadn’t even mentioned the company’s name. She claimed she’s been perfectly happy with her job and that her light-hearted comments shouldn’t (27) _________ taken seriously. A spokesperson from a workers’ union said the incident demonstrated two things: firstly, that people need to protect their privacy online and secondly, that employers should be less sensitive to criticism.

Điền vào ô 23

for

as

like

at

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct word or phrase that best fits each of the numbered blanks from 23 to 27.

SOCIAL NETWORK

A 16-year-old girl from Essex has been sacked after describing her job as boring on the social networking website, Facebook. The teenager, who had been working (23) _________ an administrative assistant at a marketing company for just three weeks, didn’t feel very enthusiastic about the duties she was asked to do. (24) _________ of moaning to her friends she decided to express her thoughts on her Facebook page to a colleague, who (25) _________ the boss’s attention to it. He immediately fired her on the (26) _________ that her public display of dissatisfaction made it impossible for her to continue working for the company. She later told newspapers she had been treated totally unfairly, especially as she hadn’t even mentioned the company’s name. She claimed she’s been perfectly happy with her job and that her light-hearted comments shouldn’t (27) _________ taken seriously. A spokesperson from a workers’ union said the incident demonstrated two things: firstly, that people need to protect their privacy online and secondly, that employers should be less sensitive to criticism.

Điền vào ô 24

Due

Regardless

Instead

In spite

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct word or phrase that best fits each of the numbered blanks from 23 to 27.

SOCIAL NETWORK

A 16-year-old girl from Essex has been sacked after describing her job as boring on the social networking website, Facebook. The teenager, who had been working (23) _________ an administrative assistant at a marketing company for just three weeks, didn’t feel very enthusiastic about the duties she was asked to do. (24) _________ of moaning to her friends she decided to express her thoughts on her Facebook page to a colleague, who (25) _________ the boss’s attention to it. He immediately fired her on the (26) _________ that her public display of dissatisfaction made it impossible for her to continue working for the company. She later told newspapers she had been treated totally unfairly, especially as she hadn’t even mentioned the company’s name. She claimed she’s been perfectly happy with her job and that her light-hearted comments shouldn’t (27) _________ taken seriously. A spokesperson from a workers’ union said the incident demonstrated two things: firstly, that people need to protect their privacy online and secondly, that employers should be less sensitive to criticism.

Điền vào ô 25

got

caught

paid

drew

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct word or phrase that best fits each of the numbered blanks from 23 to 27.

SOCIAL NETWORK

A 16-year-old girl from Essex has been sacked after describing her job as boring on the social networking website, Facebook. The teenager, who had been working (23) _________ an administrative assistant at a marketing company for just three weeks, didn’t feel very enthusiastic about the duties she was asked to do. (24) _________ of moaning to her friends she decided to express her thoughts on her Facebook page to a colleague, who (25) _________ the boss’s attention to it. He immediately fired her on the (26) _________ that her public display of dissatisfaction made it impossible for her to continue working for the company. She later told newspapers she had been treated totally unfairly, especially as she hadn’t even mentioned the company’s name. She claimed she’s been perfectly happy with her job and that her light-hearted comments shouldn’t (27) _________ taken seriously. A spokesperson from a workers’ union said the incident demonstrated two things: firstly, that people need to protect their privacy online and secondly, that employers should be less sensitive to criticism.

Điền vào ô 26

terms

condition

grounds

basis

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct word or phrase that best fits each of the numbered blanks from 23 to 27.

SOCIAL NETWORK

A 16-year-old girl from Essex has been sacked after describing her job as boring on the social networking website, Facebook. The teenager, who had been working (23) _________ an administrative assistant at a marketing company for just three weeks, didn’t feel very enthusiastic about the duties she was asked to do. (24) _________ of moaning to her friends she decided to express her thoughts on her Facebook page to a colleague, who (25) _________ the boss’s attention to it. He immediately fired her on the (26) _________ that her public display of dissatisfaction made it impossible for her to continue working for the company. She later told newspapers she had been treated totally unfairly, especially as she hadn’t even mentioned the company’s name. She claimed she’s been perfectly happy with her job and that her light-hearted comments shouldn’t (27) _________ taken seriously. A spokesperson from a workers’ union said the incident demonstrated two things: firstly, that people need to protect their privacy online and secondly, that employers should be less sensitive to criticism.

Điền vào ô 27

to be

have been

be

have

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 28 to 34.

Therapeutic cloning

Reproductive cloning involves implanting a cloned embryo into a uterus in the hope of producing a healthy foetus. A company called Clonaid claims to have successfully cloned thirteen human babies. They say that all of the babies are healthy and are in various location including Hong Kong, UK, Spain and Brazil. Clonaid states that they are using human cloning to assist infertile couples, homosexual couples and families who have lost a beloved relative.

The same technology can be used for animal cloning. If endangered species such as the giant panda and Sumatran tiger could be cloned, they could be saved from extinction. Livestock such as cows could also be cloned to allow farmers to reproduce cattle that produce the best meat and most milk. This could greatly help developing countries where cows produce significantly less meat and milk.

What does the passage mainly discuss?

How the development of technology can be monitored

How different human cloning is from animal cloning

A famous scientist working on cloning technology

Two different types of human cloning technology

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 28 to 34.

Therapeutic cloning

Reproductive cloning involves implanting a cloned embryo into a uterus in the hope of producing a healthy foetus. A company called Clonaid claims to have successfully cloned thirteen human babies. They say that all of the babies are healthy and are in various location including Hong Kong, UK, Spain and Brazil. Clonaid states that they are using human cloning to assist infertile couples, homosexual couples and families who have lost a beloved relative.

The same technology can be used for animal cloning. If endangered species such as the giant panda and Sumatran tiger could be cloned, they could be saved from extinction. Livestock such as cows could also be cloned to allow farmers to reproduce cattle that produce the best meat and most milk. This could greatly help developing countries where cows produce significantly less meat and milk.

According to the passage, which of the following is NOT true?

Cloning technology can help cure back and neck injuries.

The first dog to be cloned was in Korea

Many countries can use cloning technology to produce more meat and milk

Diabetes can’t be cured by using cloning technology

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 28 to 34.

Therapeutic cloning

Reproductive cloning involves implanting a cloned embryo into a uterus in the hope of producing a healthy foetus. A company called Clonaid claims to have successfully cloned thirteen human babies. They say that all of the babies are healthy and are in various location including Hong Kong, UK, Spain and Brazil. Clonaid states that they are using human cloning to assist infertile couples, homosexual couples and families who have lost a beloved relative.

The same technology can be used for animal cloning. If endangered species such as the giant panda and Sumatran tiger could be cloned, they could be saved from extinction. Livestock such as cows could also be cloned to allow farmers to reproduce cattle that produce the best meat and most milk. This could greatly help developing countries where cows produce significantly less meat and milk.

The word “assist” in paragraph 3 is closest in meaning to _____.

hinder

help

contribute

cure

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 28 to 34.

Therapeutic cloning

Reproductive cloning involves implanting a cloned embryo into a uterus in the hope of producing a healthy foetus. A company called Clonaid claims to have successfully cloned thirteen human babies. They say that all of the babies are healthy and are in various location including Hong Kong, UK, Spain and Brazil. Clonaid states that they are using human cloning to assist infertile couples, homosexual couples and families who have lost a beloved relative.

The same technology can be used for animal cloning. If endangered species such as the giant panda and Sumatran tiger could be cloned, they could be saved from extinction. Livestock such as cows could also be cloned to allow farmers to reproduce cattle that produce the best meat and most milk. This could greatly help developing countries where cows produce significantly less meat and milk.

The word “unveiling” in paragraph 1 is closest in meaning to _____

entrance

introduction

opening

promotion

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 28 to 34.

Therapeutic cloning

Reproductive cloning involves implanting a cloned embryo into a uterus in the hope of producing a healthy foetus. A company called Clonaid claims to have successfully cloned thirteen human babies. They say that all of the babies are healthy and are in various location including Hong Kong, UK, Spain and Brazil. Clonaid states that they are using human cloning to assist infertile couples, homosexual couples and families who have lost a beloved relative.

The same technology can be used for animal cloning. If endangered species such as the giant panda and Sumatran tiger could be cloned, they could be saved from extinction. Livestock such as cows could also be cloned to allow farmers to reproduce cattle that produce the best meat and most milk. This could greatly help developing countries where cows produce significantly less meat and milk.

According to the passage, who is King Chow?

A scientist who discovered cloning technology

A Professor of Biotechnology

A famous Parkinson’s doctor

A therapeutic cloning expert.

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 28 to 34.

Therapeutic cloning

Reproductive cloning involves implanting a cloned embryo into a uterus in the hope of producing a healthy foetus. A company called Clonaid claims to have successfully cloned thirteen human babies. They say that all of the babies are healthy and are in various location including Hong Kong, UK, Spain and Brazil. Clonaid states that they are using human cloning to assist infertile couples, homosexual couples and families who have lost a beloved relative.

The same technology can be used for animal cloning. If endangered species such as the giant panda and Sumatran tiger could be cloned, they could be saved from extinction. Livestock such as cows could also be cloned to allow farmers to reproduce cattle that produce the best meat and most milk. This could greatly help developing countries where cows produce significantly less meat and milk.

According to paragraph 4, what animals are in danger of extinction?

cows

giant pandas

all breeds of tiger

livestock

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 28 to 34.

Therapeutic cloning

Reproductive cloning involves implanting a cloned embryo into a uterus in the hope of producing a healthy foetus. A company called Clonaid claims to have successfully cloned thirteen human babies. They say that all of the babies are healthy and are in various location including Hong Kong, UK, Spain and Brazil. Clonaid states that they are using human cloning to assist infertile couples, homosexual couples and families who have lost a beloved relative.

The same technology can be used for animal cloning. If endangered species such as the giant panda and Sumatran tiger could be cloned, they could be saved from extinction. Livestock such as cows could also be cloned to allow farmers to reproduce cattle that produce the best meat and most milk. This could greatly help developing countries where cows produce significantly less meat and milk.

The word “it” in paragraph 2 refers to ______.

reproductive cloning

the development of cloning technology

Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

the first cloned dog

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 35 to 42.

THE PRAISE OF FAST FOOD

The media and a multitude of cookbook writers would have us believe that modern, fast, processed food is a disaster, and that it is a mark of sophistication to bemoan the steel roller mill and sliced white bread while yearning for stone-ground flour and a brick oven. Perhaps, we should call those scorn industrialised food, culinary Luddites, after the 19th-century English workers who rebelled against the machines that destroyed their way of life. Instead of technology, what these Luddites abhor is commercial sauces and any synthetic aid to flavouring our food.

Eating fresh, natural food was regarded with suspicion verging on horror; only the uncivilised, the poor, and the starving resorted to it. The ancient Greeks regarded the consumption of greens and root vegetables as a sign of bad times, and many succeeding civilizations believed the same. Happiness was not a verdant garden abounding in fresh fruits, but a securely locked storehouse jammed with preserved, processed foods.

What about the idea that the best food is handmade in the country? That food comes from the country goes without saying. However, the idea that country people eat better than city dwellers is preposterous. Very few of our ancestors working the land were independent peasants baking their own bread and salting down their own pig. Most were burdened with heavy taxes and rent, often paid directly by the food they produced. Many were ultimately serfs or slaves, who subsisted on what was left over; on watery soup and gritty flatbread.

The dishes we call ethnic and assume to be of peasant origin were invented for the urban, or at least urbane, aristocrats who collected the surplus. This is as true of the lasagna of northern Italy as it is of the chicken korma of Mughal Delhi, the moo shu pork of imperial China, and the pilafs and baklava of the great Ottoman palace in Istanbul. Cities have always enjoyed the best food and have invariably been the focal points of culinary innovation.

Preparing home-cooked breakfast, dinner, and tea for eight to ten people 365 days a year was servitude. Churning butter or skinning and cleaning rabbits, without the option of picking up the phone for a pizza if something went wrong, was unremitting, unforgiving toil. Not long ago, in Mexico, most women could expect to spend five hours a day kneeling at the grindstone preparing the dough for the family's tortillas.

In the first half of the 20th century, Italians embraced factory-made pasta and canned tomatoes. In the second half, Japanese women welcomed factory-made bread because they could sleep a little longer instead of getting up to make rice. As supermarkets appeared in Eastern Europe, people rejoiced at the convenience of readymade goods. Culinary modernism had proved what was wanted: food that was processed, preservable, industrial, novel, and fast, the food of the elite at a price everyone could afford. Where modern food became available, people grew taller and stronger and lived longer.

So the sunlit past of the culinary Luddites never existed and their ethos is based not on history but on a fairy tale. So what? Certainly no one would deny that an industrialised food supply has its own problems. Perhaps we should eat more fresh, natural, locally sourced, slow food. Does it matter if the history is not quite right? It matters quite a bit, I believe. If we do not understand that most people had no choice but to devote their lives to growing and cooking food, we are incapable of comprehending that modern food allows us unparalleled choices. If we urge the farmer to stay at his olive press and the housewife to remain at her stove, all so that we may eat traditionally pressed olive oil and home-cooked meals, we are assuming the mantle of the aristocrats of old. If we fail to understand how scant and monotonous most traditional diets were, we fail to appreciate the 'ethnic foods' we encounter.

Culinary Luddites are right, though, about two important things: We need to know how to prepare good food, and we need a culinary ethos. As far as good food goes, they've done us all a service by teaching us how to use the bounty delivered to us by the global economy. Their ethos, though, is another matter. Were we able to turn back the clock, as they urge, most of us would be toiling all day in the fields or the kitchen, and many of us would be starving.

The word “preposterous” in paragraph 3 is closest in meaning to ______.

sensible

popular

ridiculous

right

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 35 to 42.

THE PRAISE OF FAST FOOD

The media and a multitude of cookbook writers would have us believe that modern, fast, processed food is a disaster, and that it is a mark of sophistication to bemoan the steel roller mill and sliced white bread while yearning for stone-ground flour and a brick oven. Perhaps, we should call those scorn industrialised food, culinary Luddites, after the 19th-century English workers who rebelled against the machines that destroyed their way of life. Instead of technology, what these Luddites abhor is commercial sauces and any synthetic aid to flavouring our food.

Eating fresh, natural food was regarded with suspicion verging on horror; only the uncivilised, the poor, and the starving resorted to it. The ancient Greeks regarded the consumption of greens and root vegetables as a sign of bad times, and many succeeding civilizations believed the same. Happiness was not a verdant garden abounding in fresh fruits, but a securely locked storehouse jammed with preserved, processed foods.

What about the idea that the best food is handmade in the country? That food comes from the country goes without saying. However, the idea that country people eat better than city dwellers is preposterous. Very few of our ancestors working the land were independent peasants baking their own bread and salting down their own pig. Most were burdened with heavy taxes and rent, often paid directly by the food they produced. Many were ultimately serfs or slaves, who subsisted on what was left over; on watery soup and gritty flatbread.

The dishes we call ethnic and assume to be of peasant origin were invented for the urban, or at least urbane, aristocrats who collected the surplus. This is as true of the lasagna of northern Italy as it is of the chicken korma of Mughal Delhi, the moo shu pork of imperial China, and the pilafs and baklava of the great Ottoman palace in Istanbul. Cities have always enjoyed the best food and have invariably been the focal points of culinary innovation.

Preparing home-cooked breakfast, dinner, and tea for eight to ten people 365 days a year was servitude. Churning butter or skinning and cleaning rabbits, without the option of picking up the phone for a pizza if something went wrong, was unremitting, unforgiving toil. Not long ago, in Mexico, most women could expect to spend five hours a day kneeling at the grindstone preparing the dough for the family's tortillas.

In the first half of the 20th century, Italians embraced factory-made pasta and canned tomatoes. In the second half, Japanese women welcomed factory-made bread because they could sleep a little longer instead of getting up to make rice. As supermarkets appeared in Eastern Europe, people rejoiced at the convenience of readymade goods. Culinary modernism had proved what was wanted: food that was processed, preservable, industrial, novel, and fast, the food of the elite at a price everyone could afford. Where modern food became available, people grew taller and stronger and lived longer.

So the sunlit past of the culinary Luddites never existed and their ethos is based not on history but on a fairy tale. So what? Certainly no one would deny that an industrialised food supply has its own problems. Perhaps we should eat more fresh, natural, locally sourced, slow food. Does it matter if the history is not quite right? It matters quite a bit, I believe. If we do not understand that most people had no choice but to devote their lives to growing and cooking food, we are incapable of comprehending that modern food allows us unparalleled choices. If we urge the farmer to stay at his olive press and the housewife to remain at her stove, all so that we may eat traditionally pressed olive oil and home-cooked meals, we are assuming the mantle of the aristocrats of old. If we fail to understand how scant and monotonous most traditional diets were, we fail to appreciate the 'ethnic foods' we encounter.

Culinary Luddites are right, though, about two important things: We need to know how to prepare good food, and we need a culinary ethos. As far as good food goes, they've done us all a service by teaching us how to use the bounty delivered to us by the global economy. Their ethos, though, is another matter. Were we able to turn back the clock, as they urge, most of us would be toiling all day in the fields or the kitchen, and many of us would be starving.

Which of the following is NOT an important factor mentioned in paragraphs 5 and 6?

the development of take-away food as an option

the arduous nature of food preparation before mass-production

the global benefits of industrialised food production

the range of advantages that industrialised food production had

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 35 to 42.

THE PRAISE OF FAST FOOD

The media and a multitude of cookbook writers would have us believe that modern, fast, processed food is a disaster, and that it is a mark of sophistication to bemoan the steel roller mill and sliced white bread while yearning for stone-ground flour and a brick oven. Perhaps, we should call those scorn industrialised food, culinary Luddites, after the 19th-century English workers who rebelled against the machines that destroyed their way of life. Instead of technology, what these Luddites abhor is commercial sauces and any synthetic aid to flavouring our food.

Eating fresh, natural food was regarded with suspicion verging on horror; only the uncivilised, the poor, and the starving resorted to it. The ancient Greeks regarded the consumption of greens and root vegetables as a sign of bad times, and many succeeding civilizations believed the same. Happiness was not a verdant garden abounding in fresh fruits, but a securely locked storehouse jammed with preserved, processed foods.

What about the idea that the best food is handmade in the country? That food comes from the country goes without saying. However, the idea that country people eat better than city dwellers is preposterous. Very few of our ancestors working the land were independent peasants baking their own bread and salting down their own pig. Most were burdened with heavy taxes and rent, often paid directly by the food they produced. Many were ultimately serfs or slaves, who subsisted on what was left over; on watery soup and gritty flatbread.

The dishes we call ethnic and assume to be of peasant origin were invented for the urban, or at least urbane, aristocrats who collected the surplus. This is as true of the lasagna of northern Italy as it is of the chicken korma of Mughal Delhi, the moo shu pork of imperial China, and the pilafs and baklava of the great Ottoman palace in Istanbul. Cities have always enjoyed the best food and have invariably been the focal points of culinary innovation.

Preparing home-cooked breakfast, dinner, and tea for eight to ten people 365 days a year was servitude. Churning butter or skinning and cleaning rabbits, without the option of picking up the phone for a pizza if something went wrong, was unremitting, unforgiving toil. Not long ago, in Mexico, most women could expect to spend five hours a day kneeling at the grindstone preparing the dough for the family's tortillas.

In the first half of the 20th century, Italians embraced factory-made pasta and canned tomatoes. In the second half, Japanese women welcomed factory-made bread because they could sleep a little longer instead of getting up to make rice. As supermarkets appeared in Eastern Europe, people rejoiced at the convenience of readymade goods. Culinary modernism had proved what was wanted: food that was processed, preservable, industrial, novel, and fast, the food of the elite at a price everyone could afford. Where modern food became available, people grew taller and stronger and lived longer.

So the sunlit past of the culinary Luddites never existed and their ethos is based not on history but on a fairy tale. So what? Certainly no one would deny that an industrialised food supply has its own problems. Perhaps we should eat more fresh, natural, locally sourced, slow food. Does it matter if the history is not quite right? It matters quite a bit, I believe. If we do not understand that most people had no choice but to devote their lives to growing and cooking food, we are incapable of comprehending that modern food allows us unparalleled choices. If we urge the farmer to stay at his olive press and the housewife to remain at her stove, all so that we may eat traditionally pressed olive oil and home-cooked meals, we are assuming the mantle of the aristocrats of old. If we fail to understand how scant and monotonous most traditional diets were, we fail to appreciate the 'ethnic foods' we encounter.

Culinary Luddites are right, though, about two important things: We need to know how to prepare good food, and we need a culinary ethos. As far as good food goes, they've done us all a service by teaching us how to use the bounty delivered to us by the global economy. Their ethos, though, is another matter. Were we able to turn back the clock, as they urge, most of us would be toiling all day in the fields or the kitchen, and many of us would be starving.

What is the overall point that the writer makes in the reading passage?

People should learn the history of the food they consume.

Criticism of industrial food production is largely misplaced

Modem industrial food is generally superior to raw and natural food

People should be more grateful for the range of foods they can now choose from.

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 35 to 42.

THE PRAISE OF FAST FOOD

The media and a multitude of cookbook writers would have us believe that modern, fast, processed food is a disaster, and that it is a mark of sophistication to bemoan the steel roller mill and sliced white bread while yearning for stone-ground flour and a brick oven. Perhaps, we should call those scorn industrialised food, culinary Luddites, after the 19th-century English workers who rebelled against the machines that destroyed their way of life. Instead of technology, what these Luddites abhor is commercial sauces and any synthetic aid to flavouring our food.

Eating fresh, natural food was regarded with suspicion verging on horror; only the uncivilised, the poor, and the starving resorted to it. The ancient Greeks regarded the consumption of greens and root vegetables as a sign of bad times, and many succeeding civilizations believed the same. Happiness was not a verdant garden abounding in fresh fruits, but a securely locked storehouse jammed with preserved, processed foods.

What about the idea that the best food is handmade in the country? That food comes from the country goes without saying. However, the idea that country people eat better than city dwellers is preposterous. Very few of our ancestors working the land were independent peasants baking their own bread and salting down their own pig. Most were burdened with heavy taxes and rent, often paid directly by the food they produced. Many were ultimately serfs or slaves, who subsisted on what was left over; on watery soup and gritty flatbread.

The dishes we call ethnic and assume to be of peasant origin were invented for the urban, or at least urbane, aristocrats who collected the surplus. This is as true of the lasagna of northern Italy as it is of the chicken korma of Mughal Delhi, the moo shu pork of imperial China, and the pilafs and baklava of the great Ottoman palace in Istanbul. Cities have always enjoyed the best food and have invariably been the focal points of culinary innovation.

Preparing home-cooked breakfast, dinner, and tea for eight to ten people 365 days a year was servitude. Churning butter or skinning and cleaning rabbits, without the option of picking up the phone for a pizza if something went wrong, was unremitting, unforgiving toil. Not long ago, in Mexico, most women could expect to spend five hours a day kneeling at the grindstone preparing the dough for the family's tortillas.

In the first half of the 20th century, Italians embraced factory-made pasta and canned tomatoes. In the second half, Japanese women welcomed factory-made bread because they could sleep a little longer instead of getting up to make rice. As supermarkets appeared in Eastern Europe, people rejoiced at the convenience of readymade goods. Culinary modernism had proved what was wanted: food that was processed, preservable, industrial, novel, and fast, the food of the elite at a price everyone could afford. Where modern food became available, people grew taller and stronger and lived longer.

So the sunlit past of the culinary Luddites never existed and their ethos is based not on history but on a fairy tale. So what? Certainly no one would deny that an industrialised food supply has its own problems. Perhaps we should eat more fresh, natural, locally sourced, slow food. Does it matter if the history is not quite right? It matters quite a bit, I believe. If we do not understand that most people had no choice but to devote their lives to growing and cooking food, we are incapable of comprehending that modern food allows us unparalleled choices. If we urge the farmer to stay at his olive press and the housewife to remain at her stove, all so that we may eat traditionally pressed olive oil and home-cooked meals, we are assuming the mantle of the aristocrats of old. If we fail to understand how scant and monotonous most traditional diets were, we fail to appreciate the 'ethnic foods' we encounter.

Culinary Luddites are right, though, about two important things: We need to know how to prepare good food, and we need a culinary ethos. As far as good food goes, they've done us all a service by teaching us how to use the bounty delivered to us by the global economy. Their ethos, though, is another matter. Were we able to turn back the clock, as they urge, most of us would be toiling all day in the fields or the kitchen, and many of us would be starving.

The word “its” in paragraph 7 refers to ______.

food supply’s

fairy tale’s

history’s

sunlit past’s

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 35 to 42.

THE PRAISE OF FAST FOOD

The media and a multitude of cookbook writers would have us believe that modern, fast, processed food is a disaster, and that it is a mark of sophistication to bemoan the steel roller mill and sliced white bread while yearning for stone-ground flour and a brick oven. Perhaps, we should call those scorn industrialised food, culinary Luddites, after the 19th-century English workers who rebelled against the machines that destroyed their way of life. Instead of technology, what these Luddites abhor is commercial sauces and any synthetic aid to flavouring our food.

Eating fresh, natural food was regarded with suspicion verging on horror; only the uncivilised, the poor, and the starving resorted to it. The ancient Greeks regarded the consumption of greens and root vegetables as a sign of bad times, and many succeeding civilizations believed the same. Happiness was not a verdant garden abounding in fresh fruits, but a securely locked storehouse jammed with preserved, processed foods.

What about the idea that the best food is handmade in the country? That food comes from the country goes without saying. However, the idea that country people eat better than city dwellers is preposterous. Very few of our ancestors working the land were independent peasants baking their own bread and salting down their own pig. Most were burdened with heavy taxes and rent, often paid directly by the food they produced. Many were ultimately serfs or slaves, who subsisted on what was left over; on watery soup and gritty flatbread.

The dishes we call ethnic and assume to be of peasant origin were invented for the urban, or at least urbane, aristocrats who collected the surplus. This is as true of the lasagna of northern Italy as it is of the chicken korma of Mughal Delhi, the moo shu pork of imperial China, and the pilafs and baklava of the great Ottoman palace in Istanbul. Cities have always enjoyed the best food and have invariably been the focal points of culinary innovation.

Preparing home-cooked breakfast, dinner, and tea for eight to ten people 365 days a year was servitude. Churning butter or skinning and cleaning rabbits, without the option of picking up the phone for a pizza if something went wrong, was unremitting, unforgiving toil. Not long ago, in Mexico, most women could expect to spend five hours a day kneeling at the grindstone preparing the dough for the family's tortillas.

In the first half of the 20th century, Italians embraced factory-made pasta and canned tomatoes. In the second half, Japanese women welcomed factory-made bread because they could sleep a little longer instead of getting up to make rice. As supermarkets appeared in Eastern Europe, people rejoiced at the convenience of readymade goods. Culinary modernism had proved what was wanted: food that was processed, preservable, industrial, novel, and fast, the food of the elite at a price everyone could afford. Where modern food became available, people grew taller and stronger and lived longer.

So the sunlit past of the culinary Luddites never existed and their ethos is based not on history but on a fairy tale. So what? Certainly no one would deny that an industrialised food supply has its own problems. Perhaps we should eat more fresh, natural, locally sourced, slow food. Does it matter if the history is not quite right? It matters quite a bit, I believe. If we do not understand that most people had no choice but to devote their lives to growing and cooking food, we are incapable of comprehending that modern food allows us unparalleled choices. If we urge the farmer to stay at his olive press and the housewife to remain at her stove, all so that we may eat traditionally pressed olive oil and home-cooked meals, we are assuming the mantle of the aristocrats of old. If we fail to understand how scant and monotonous most traditional diets were, we fail to appreciate the 'ethnic foods' we encounter.

Culinary Luddites are right, though, about two important things: We need to know how to prepare good food, and we need a culinary ethos. As far as good food goes, they've done us all a service by teaching us how to use the bounty delivered to us by the global economy. Their ethos, though, is another matter. Were we able to turn back the clock, as they urge, most of us would be toiling all day in the fields or the kitchen, and many of us would be starving.

What does the writer say about peasants?

They created imaginative soup and flatbread dishes

Much of what they produced went to a landowner.

They were largely self-sufficient

They had a better diet than most people living in cities.

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 35 to 42.

THE PRAISE OF FAST FOOD

The media and a multitude of cookbook writers would have us believe that modern, fast, processed food is a disaster, and that it is a mark of sophistication to bemoan the steel roller mill and sliced white bread while yearning for stone-ground flour and a brick oven. Perhaps, we should call those scorn industrialised food, culinary Luddites, after the 19th-century English workers who rebelled against the machines that destroyed their way of life. Instead of technology, what these Luddites abhor is commercial sauces and any synthetic aid to flavouring our food.

Eating fresh, natural food was regarded with suspicion verging on horror; only the uncivilised, the poor, and the starving resorted to it. The ancient Greeks regarded the consumption of greens and root vegetables as a sign of bad times, and many succeeding civilizations believed the same. Happiness was not a verdant garden abounding in fresh fruits, but a securely locked storehouse jammed with preserved, processed foods.

What about the idea that the best food is handmade in the country? That food comes from the country goes without saying. However, the idea that country people eat better than city dwellers is preposterous. Very few of our ancestors working the land were independent peasants baking their own bread and salting down their own pig. Most were burdened with heavy taxes and rent, often paid directly by the food they produced. Many were ultimately serfs or slaves, who subsisted on what was left over; on watery soup and gritty flatbread.

The dishes we call ethnic and assume to be of peasant origin were invented for the urban, or at least urbane, aristocrats who collected the surplus. This is as true of the lasagna of northern Italy as it is of the chicken korma of Mughal Delhi, the moo shu pork of imperial China, and the pilafs and baklava of the great Ottoman palace in Istanbul. Cities have always enjoyed the best food and have invariably been the focal points of culinary innovation.

Preparing home-cooked breakfast, dinner, and tea for eight to ten people 365 days a year was servitude. Churning butter or skinning and cleaning rabbits, without the option of picking up the phone for a pizza if something went wrong, was unremitting, unforgiving toil. Not long ago, in Mexico, most women could expect to spend five hours a day kneeling at the grindstone preparing the dough for the family's tortillas.

In the first half of the 20th century, Italians embraced factory-made pasta and canned tomatoes. In the second half, Japanese women welcomed factory-made bread because they could sleep a little longer instead of getting up to make rice. As supermarkets appeared in Eastern Europe, people rejoiced at the convenience of readymade goods. Culinary modernism had proved what was wanted: food that was processed, preservable, industrial, novel, and fast, the food of the elite at a price everyone could afford. Where modern food became available, people grew taller and stronger and lived longer.

So the sunlit past of the culinary Luddites never existed and their ethos is based not on history but on a fairy tale. So what? Certainly no one would deny that an industrialised food supply has its own problems. Perhaps we should eat more fresh, natural, locally sourced, slow food. Does it matter if the history is not quite right? It matters quite a bit, I believe. If we do not understand that most people had no choice but to devote their lives to growing and cooking food, we are incapable of comprehending that modern food allows us unparalleled choices. If we urge the farmer to stay at his olive press and the housewife to remain at her stove, all so that we may eat traditionally pressed olive oil and home-cooked meals, we are assuming the mantle of the aristocrats of old. If we fail to understand how scant and monotonous most traditional diets were, we fail to appreciate the 'ethnic foods' we encounter.

Culinary Luddites are right, though, about two important things: We need to know how to prepare good food, and we need a culinary ethos. As far as good food goes, they've done us all a service by teaching us how to use the bounty delivered to us by the global economy. Their ethos, though, is another matter. Were we able to turn back the clock, as they urge, most of us would be toiling all day in the fields or the kitchen, and many of us would be starving.

What is an important point the writer wishes to make in paragraph 7?

People need to have a balanced diet.

There are disadvantages to modem food production as well as advantages.

People everywhere now have a huge range of food to choose from.

Demand for food that is traditionally produced exploits the people that produce it.

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 35 to 42.

THE PRAISE OF FAST FOOD

The media and a multitude of cookbook writers would have us believe that modern, fast, processed food is a disaster, and that it is a mark of sophistication to bemoan the steel roller mill and sliced white bread while yearning for stone-ground flour and a brick oven. Perhaps, we should call those scorn industrialised food, culinary Luddites, after the 19th-century English workers who rebelled against the machines that destroyed their way of life. Instead of technology, what these Luddites abhor is commercial sauces and any synthetic aid to flavouring our food.

Eating fresh, natural food was regarded with suspicion verging on horror; only the uncivilised, the poor, and the starving resorted to it. The ancient Greeks regarded the consumption of greens and root vegetables as a sign of bad times, and many succeeding civilizations believed the same. Happiness was not a verdant garden abounding in fresh fruits, but a securely locked storehouse jammed with preserved, processed foods.

What about the idea that the best food is handmade in the country? That food comes from the country goes without saying. However, the idea that country people eat better than city dwellers is preposterous. Very few of our ancestors working the land were independent peasants baking their own bread and salting down their own pig. Most were burdened with heavy taxes and rent, often paid directly by the food they produced. Many were ultimately serfs or slaves, who subsisted on what was left over; on watery soup and gritty flatbread.

The dishes we call ethnic and assume to be of peasant origin were invented for the urban, or at least urbane, aristocrats who collected the surplus. This is as true of the lasagna of northern Italy as it is of the chicken korma of Mughal Delhi, the moo shu pork of imperial China, and the pilafs and baklava of the great Ottoman palace in Istanbul. Cities have always enjoyed the best food and have invariably been the focal points of culinary innovation.

Preparing home-cooked breakfast, dinner, and tea for eight to ten people 365 days a year was servitude. Churning butter or skinning and cleaning rabbits, without the option of picking up the phone for a pizza if something went wrong, was unremitting, unforgiving toil. Not long ago, in Mexico, most women could expect to spend five hours a day kneeling at the grindstone preparing the dough for the family's tortillas.

In the first half of the 20th century, Italians embraced factory-made pasta and canned tomatoes. In the second half, Japanese women welcomed factory-made bread because they could sleep a little longer instead of getting up to make rice. As supermarkets appeared in Eastern Europe, people rejoiced at the convenience of readymade goods. Culinary modernism had proved what was wanted: food that was processed, preservable, industrial, novel, and fast, the food of the elite at a price everyone could afford. Where modern food became available, people grew taller and stronger and lived longer.

So the sunlit past of the culinary Luddites never existed and their ethos is based not on history but on a fairy tale. So what? Certainly no one would deny that an industrialised food supply has its own problems. Perhaps we should eat more fresh, natural, locally sourced, slow food. Does it matter if the history is not quite right? It matters quite a bit, I believe. If we do not understand that most people had no choice but to devote their lives to growing and cooking food, we are incapable of comprehending that modern food allows us unparalleled choices. If we urge the farmer to stay at his olive press and the housewife to remain at her stove, all so that we may eat traditionally pressed olive oil and home-cooked meals, we are assuming the mantle of the aristocrats of old. If we fail to understand how scant and monotonous most traditional diets were, we fail to appreciate the 'ethnic foods' we encounter.

Culinary Luddites are right, though, about two important things: We need to know how to prepare good food, and we need a culinary ethos. As far as good food goes, they've done us all a service by teaching us how to use the bounty delivered to us by the global economy. Their ethos, though, is another matter. Were we able to turn back the clock, as they urge, most of us would be toiling all day in the fields or the kitchen, and many of us would be starving.

Lasagna is an example of a dish ______.

that tastes like dishes from several other countries

that was only truly popular in northern Italy

invented by peasants

created for wealthy city-dwellers

Read the following passage and mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the correct answer to each of the questions from 35 to 42.

THE PRAISE OF FAST FOOD

The media and a multitude of cookbook writers would have us believe that modern, fast, processed food is a disaster, and that it is a mark of sophistication to bemoan the steel roller mill and sliced white bread while yearning for stone-ground flour and a brick oven. Perhaps, we should call those scorn industrialised food, culinary Luddites, after the 19th-century English workers who rebelled against the machines that destroyed their way of life. Instead of technology, what these Luddites abhor is commercial sauces and any synthetic aid to flavouring our food.

Eating fresh, natural food was regarded with suspicion verging on horror; only the uncivilised, the poor, and the starving resorted to it. The ancient Greeks regarded the consumption of greens and root vegetables as a sign of bad times, and many succeeding civilizations believed the same. Happiness was not a verdant garden abounding in fresh fruits, but a securely locked storehouse jammed with preserved, processed foods.

What about the idea that the best food is handmade in the country? That food comes from the country goes without saying. However, the idea that country people eat better than city dwellers is preposterous. Very few of our ancestors working the land were independent peasants baking their own bread and salting down their own pig. Most were burdened with heavy taxes and rent, often paid directly by the food they produced. Many were ultimately serfs or slaves, who subsisted on what was left over; on watery soup and gritty flatbread.

The dishes we call ethnic and assume to be of peasant origin were invented for the urban, or at least urbane, aristocrats who collected the surplus. This is as true of the lasagna of northern Italy as it is of the chicken korma of Mughal Delhi, the moo shu pork of imperial China, and the pilafs and baklava of the great Ottoman palace in Istanbul. Cities have always enjoyed the best food and have invariably been the focal points of culinary innovation.

Preparing home-cooked breakfast, dinner, and tea for eight to ten people 365 days a year was servitude. Churning butter or skinning and cleaning rabbits, without the option of picking up the phone for a pizza if something went wrong, was unremitting, unforgiving toil. Not long ago, in Mexico, most women could expect to spend five hours a day kneeling at the grindstone preparing the dough for the family's tortillas.

In the first half of the 20th century, Italians embraced factory-made pasta and canned tomatoes. In the second half, Japanese women welcomed factory-made bread because they could sleep a little longer instead of getting up to make rice. As supermarkets appeared in Eastern Europe, people rejoiced at the convenience of readymade goods. Culinary modernism had proved what was wanted: food that was processed, preservable, industrial, novel, and fast, the food of the elite at a price everyone could afford. Where modern food became available, people grew taller and stronger and lived longer.

So the sunlit past of the culinary Luddites never existed and their ethos is based not on history but on a fairy tale. So what? Certainly no one would deny that an industrialised food supply has its own problems. Perhaps we should eat more fresh, natural, locally sourced, slow food. Does it matter if the history is not quite right? It matters quite a bit, I believe. If we do not understand that most people had no choice but to devote their lives to growing and cooking food, we are incapable of comprehending that modern food allows us unparalleled choices. If we urge the farmer to stay at his olive press and the housewife to remain at her stove, all so that we may eat traditionally pressed olive oil and home-cooked meals, we are assuming the mantle of the aristocrats of old. If we fail to understand how scant and monotonous most traditional diets were, we fail to appreciate the 'ethnic foods' we encounter.

Culinary Luddites are right, though, about two important things: We need to know how to prepare good food, and we need a culinary ethos. As far as good food goes, they've done us all a service by teaching us how to use the bounty delivered to us by the global economy. Their ethos, though, is another matter. Were we able to turn back the clock, as they urge, most of us would be toiling all day in the fields or the kitchen, and many of us would be starving.

The word “servitude” in paragraph 5 is closest in meaning to ______.

attitude

enslavement

capability

liberty

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the underlined part that needs correction in each of the following questions.

Many people who live near the ocean depend on it as a source of food, recreation, and to have economic opportunities.

depend on

food

recreation

to have economic

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the underlined part that needs correction in each of the following questions.

The techniques of science and magic are quite different, but their basic aims – to understand and control nature, they are very similar.

magic

different

to understand

they are

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the underlined part that needs correction in each of the following questions.

The various parts of the body require so different surgical skills that many surgical specialties have developed.

they are

so

surgical

many

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the sentence that is closest in meaning to each of the following questions.

It’s a waste of time asking Peter for help because he is too busy.

Peter is too busy that he can’t help anyone.

You shouldn’t ask Peter for help as he will refuse.

There’s no point asking Peter for help because he is too busy

It takes your time when you ask Peter for help because he is too busy

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the sentence that is closest in meaning to each of the following questions.

“I’m sorry for not keeping my promise, Mum!” said John.

John said he was sorry for not keeping his promise.

John apologised to his Mum for breaking his promise.

John apologised his Mum because he didn’t keep his promise.

John felt sorry for his mum’s not keeping her promise.

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the sentence that is closest in meaning to each of the following questions.

We’re still hesitating about which school our son ought to go to.

We had great difficulty deciding upon which school our son should attend

We haven’t yet decided where we should send our son to school

We are not sure whether we should let our son choose a school for himself.

We won’t send our son to any school unless we are certain that it is the one we want.

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the sentence that best combines each pair of sentences in the following questions.

I’d like to blame you. However, I know I can’t.

Much as I’d like to blame you, I know I can’t.

However much would I like to blame you, I know I can’t.

Since I know I can’t, I’d like to blame you

Though I wouldn’t like to blame you, I know I can’t

Mark the letter A, B, C, or D on your answer sheet to indicate the sentence that best combines each pair of sentences in the following questions.

My brother couldn’t speak a word. He could do that when he turned three.

Not until my brother turned three he could speak a word.

It was before my brother turned three that he could speak a word.

Not until my brother turned three could he speak a word.

My brother couldn’t speak a word even after he turned three.